1

SIGNALS

AND

SYSTEMS

1.0

INTRODUCTION

As described in the Foreword, the intuitive notions

of

signals and systems arise in a rich va-

riety

of

contexts. Moreover, as we will see in this book, there is an analytical

framework-

that is, a language for describing signals and systems and an extremely powerful set

of

tools

for analyzing

them-that

applies equally well

to

problems

in

many fields. In this chapter,

we begin our development of the analytical framework for signals and systems by intro-

ducing their mathematical description and representations. In the chapters that follow, we

build on this foundation in order

to

develop and describe additional concepts and methods

that add considerably both

to

our understanding

of

signals and systems and

to

our ability

to

analyze and solve problems involving signals and systems that arise in a broad array

of

applications.

1.

1

CONTINUOUS-TIME

AND

DISCRETE-TIME SIGNALS

1 . 1 . 1 Examples

and

Mathematical

Representation

Signals may describe a wide variety

of

physical phenomena. Although signals can be rep-

resented in many ways, in all cases the information in a signal is contained in a pattern

of

variations

of

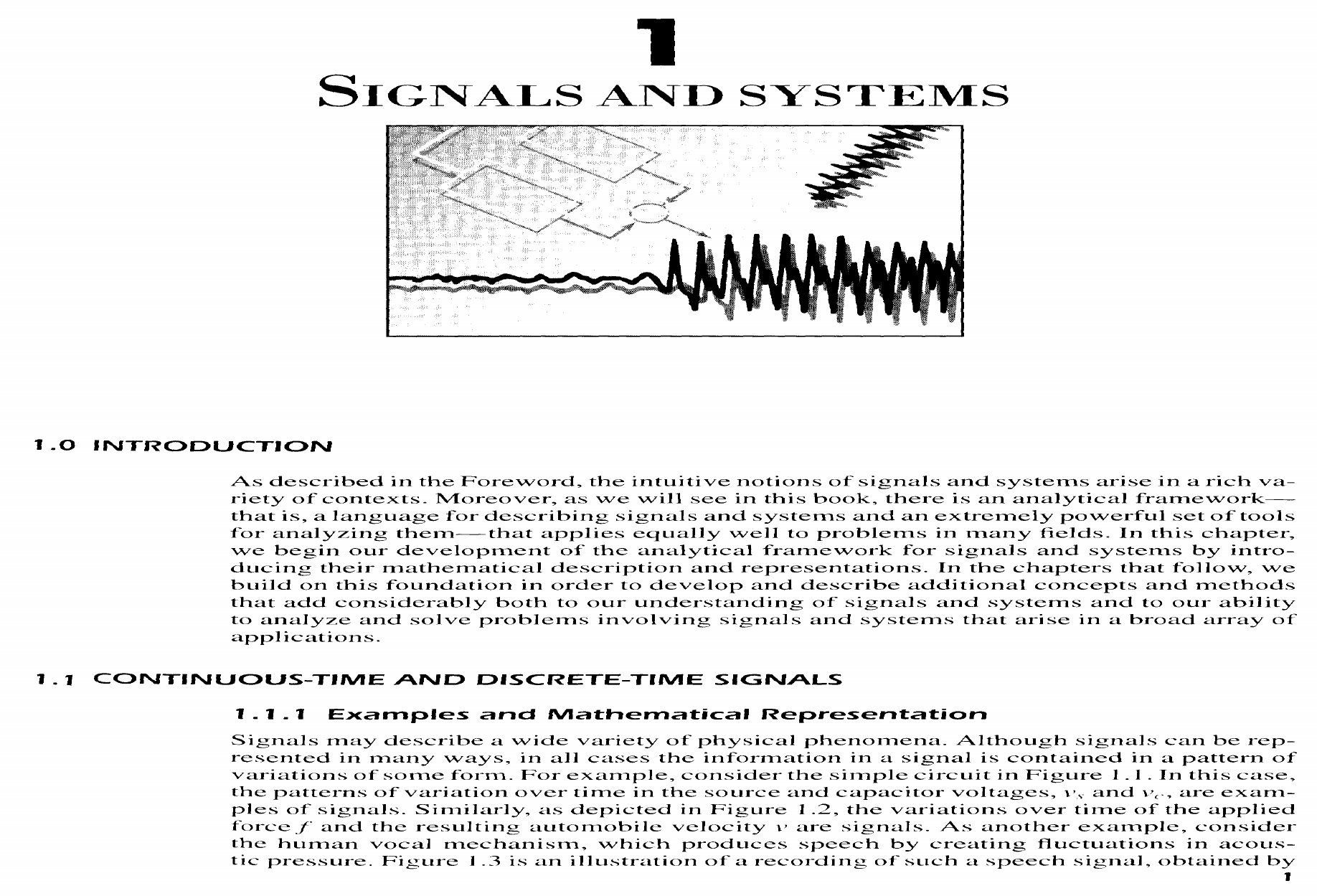

some form. For example, consider the simple circuit in Figure 1.1. In this case,

the patterns

of

variation over time in the source and capacitor voltages,

v,

and

Vc,

are exam-

ples

of

signals. Similarly, as depicted in Figure 1.2, the variations over time

of

the applied

force

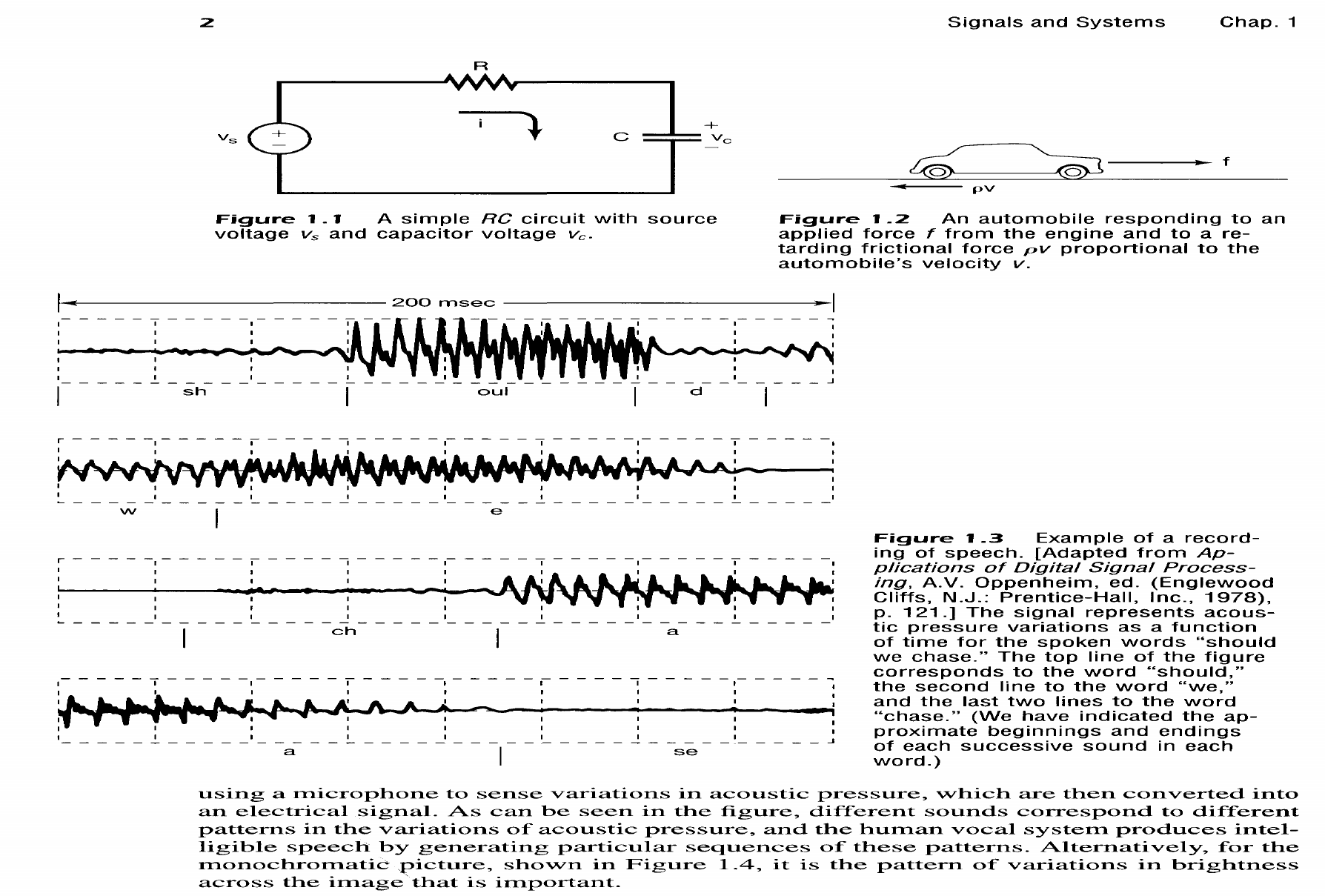

f and the resulting automobile velocity v are signals. As another example, consider

the human vocal mechanism, which produces speech by creating fluctuations in acous-

tic pressure. Figure

1.3

is

an illustration

of

a recording

of

such a speech signal, obtained by

1

2

Signals

and

Systems

Chap.

1

R

c

~pv

Figure 1. 1 A

simple

RC

circuit

with

source

voltage

Vs

and

capacitor

voltage

Vc.

Figure 1

.2

An

automobile

responding

to

an

applied

force

t

from

the

engine

and

to

a

re-

tarding

frictional

force

pv

proportional

to

the

automobile's

velocity

v.

~-------------------200msec--------------------~

I I I I

1

_____

.!_

_____

1

_____

!._

_____

1

__________

~

_____

I

_____

J

j

sh

oul d

r - - - -

-~-

- - - - I - - - - I - - - - -

~-

- - - - I - - - -

-~-

- - - - I - - - - -~

I

I

I I I I I I I

~-------------------------------------------

w

e

r - - - -

-~-

- - - - I - - - - I - - - - -

~-

- - - - I - - - -

-~-

- - - - I - - - -

-~

I I I

I

~

_____

1

_____

~

____

~

_____

1

_____

.!_

_____

I

_____

~

_____

I

ch a

I I I I

1

_____

~

_____

1

_____

~

_____

1

_____

I

_____

~

_____

1

_____

J

a

I

se

Figure

1.3

Example

of

a

record-

ing

of

speech.

[Adapted

from

Ap-

plications

of

Digital

Signal

Process-

ing,

A.V.

Oppenheim,

ed.

(Englewood

Cliffs,

N.J.:

Prentice-Hall,

Inc.,

1978),

p.

121.]

The

signal

represents

acous-

tic

pressure

variations

as

a

function

of

time

for

the

spoken

words

"should

we

chase."

The

top

line

of

the

figure

corresponds

to

the

word

"should,"

the

second

line

to

the

word

"we,"

and

the

last

two

lines

to

the

word

"chase."

(We

have

indicated

the

ap-

proximate

beginnings

and

endings

of

each

successive

sound

in

each

word.)

using a microphone

to

sense variations in acoustic pressure, which are then converted into

an electrical signal. As can be seen in the figure, different sounds correspond

to

different

patterns in the variations of acoustic pressure, and the human vocal system produces intel-

ligible speech by generating particular sequences of these patterns. Alternatively, for the

monochromatic picture, shown in Figure 1.4, it is the pattern

of

variations in brightness

across the image, that is important.